Footnotes:

The Great War. The War To End All Wars. World War I was the first war in human history to span the entire globe. Between 1914 and 1918, every place on Earth seemed to be burning. Those who lived through it believed they might be witnessing the end of days. How odd, then, that at the outset of the conflict, people flocked to the fight with cheer and enthusiasm. World War I started out as “the war that would be over by Christmas.” How could all of Europe have misread the situation so grievously?

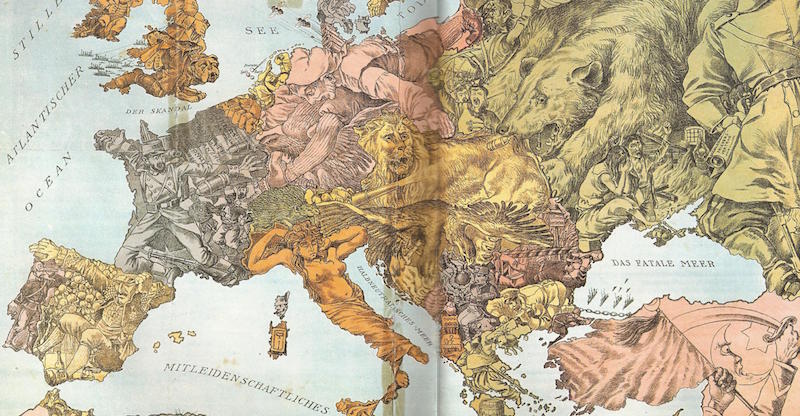

In today’s exhibit, we examine the attitudes and misconceptions that pushed the world over the edge. In order to understand it all, though, it helps to have a few maps. In 1914, Europe looked like this:

The various European empires of the day were rife with tension, existing in a delicate balance stitched together by a complicated web of agreements to defend or attack each other if one country or another made any sudden movements. And there was one empire above all that that was very twitchy: Austria-Hungary.

The Austro-Hungarian Empire was composed of lots of smaller nations that had been brought in under one flag, some of them against their will. Two of these annexed states, Bosnia and Herzegovina, were part of the Slavic nations to the south. The Slavic nations and Balkan States had been oppressed by the Ottoman Empire for years and had just recently won their independence, only to have the Austro-Hungarians come in and start claiming all over their homes as its own territory. Serbia, which bordered Austria-Hungary, was particularly loud and angry about it.

Austria-Hungary was several times larger than Serbia, though, and had half a mind to shut them up through violence. The empire figured it could destroy Serbia, or better yet, annex them. And here’s where things get complex:

Germany had ambitions to bring all of Europe into a state of German cultural hegemony. They hoped even to spread their own empire as far as Africa and the Middle East. This meant bridging the territory between themselves and the Mediterranean. That meant Germany needed Austria-Hungary’s help to control the nations to the south, so they formed an alliance.

In the west, France and the United Kingdom were basically frenemies during this time. Each had agreed to help each other out in the event of a conflict, but each secretly had plans for invading the other in their back pockets just in case.

In 1871, Germany had beaten France in the Prussian War, leaving decades-old bad blood between them. France decided to ally itself with Russia, Germany’s much larger neighbor to the east. Why? Well, Russia had been making large technological strides of its own in recent years including unifying and standardizing their railway system.

This made German leadership very nervous, because they felt that if massive Russia was able to catch up to the rest of the world technologically, it would be unbeatable in a fight. Germany believed that if ever there was a time to go to war with Russia, it was now before Russia stood as tall as everyone else. Plus, by being cool with France, Russia also ended up on friendly terms with the UK by association.

England famously had the greatest navy in the world, one that nobody wanted a piece of. German emperor Kaiser Wilhelm II, however, was convinced that England was nothing without its navy. He ordered the German military to construct its own armada of battleships to go toe to toe with England if it ever came to it. Make no mistake, this was meant to be a big middle finger to the Brits.

Germany’s navy came at a huge cost: about one third of their defense budget. This meant that if a land war broke out, they could no longer afford to defend against France in the West and Russia in the East. At least, not at the same time. If Germany fought, it was going to be an uphill battle.

But the Germans had a friend in the Ottoman Empire in the Middle East, with whom they had some pretty solid trade going. Austria-Hungary was between Germany and the Ottomans, though, hence its importance to German plans. And between Austria-Hungary and the Ottomans were the Slavic and Balkan states, which brings us back around to Serbia.

The Austro-Hungarian Empire was getting rabid over all the anti-Austrian sentiment Serbia was drumming up. They were itching for a war. But if they started one, Germany was obligated to help. Germany wanted that connecting tissue through to Africa and the Middle East though, so they declared that they’d back Austria if war broke out.

Austria’s excuse to fight the war came in the form of the Archduke Franz Ferdinand. Franz Ferdinand was the empire’s crown prince, next in line for the throne. On his and his wife’s 14th anniversary, the couple decided to take a day trip to Sarajevo, in former Bosnia, which you’ll recall the Austrians annexed. The former Bosnians had strong, lingering anger over the loss of their agency, enough so that a rogue secret society had the archduke assassinated while he was out with his wife on June 28th, 1914.

More on Franz Ferdinand:

More on the bumbling assassination plot:

Franz Ferdinand, it turns out, was a guy nobody really liked, but Austria-Hungary used his death as springboard to declare war. They barely took time to bury him before mobilizing to invade Serbia. This meant Germany was also going to war.

Concerned that they’d have to fight massive battles in both the east and west, German high command devised a strategy to cut through Belgium and take Paris before France could react, then swing back and focus all their forces on Russia. They estimated they could knock France out of the fight in 6 weeks. The strategy was known as the Schlieffen Plan:

Now, as history has taught us, this didn’t work out. We know now that this is partly because most of the military leaders of the day had no military experience. The last major European war had been over 40 years prior. Most of the generals and emperors leading the charge romanticized war and glory without having fought a day in their lives. This would prove fatal for countless men and even the empires themselves in the end, because these leaders were hopelessly out of touch with modern warfare.

Though it may seem odd in hindsight, every side in the fight at the time thought they were going to win and win fast. The Serbians were fighting for freedom. The Austrians were bigger and scarier than Serbia. Russia was biggest and scariest. The Germans had the superior weaponry. The French were raring for payback against Germany. The British felt they had a moral obligation to stop Austria and Germany. This had men volunteering to fight in droves.

Remember, it had been decades since Europe had experienced a long war. Even the largest war in recent memory, the Prussian War, had only lasted a year. People everywhere joked that they’d be home for Christmas. Most military leaders had no concept of a long war, and all of their strategies favored quick, decisive action. It soon became clear, however, that everyone had very different ideas about how war ought to be fought.

The old way of waging war in straight lines and with abundant fanfare collided with mounted machine guns and poison gas. Infantry met with artillery. Bayonets clashed with flamethrowers.

Aviation technology went from this:

To this:

The seemingly invincible British Navy would be sent straight to the seabed by phantoms just beneath the surface:

But the real clincher, the factor that truly caused the war to drag on into oblivion was the introduction of trench warfare:

Each side had some weapon or device that their opponents had never seen before, and the results were devastating. Hundreds of thousands of men died in the first month of the war alone, and by Christmas the count would reach nearly a million. The reality that this was like no war the world had ever seen set in almost immediately, and if the soldiers became disillusioned, most of them wouldn’t live long enough to take it up with the leadership.

That leadership would fall apart within months. German Chief of Staff Helmuth Von Moltke and Austrian Chief of Staff Conrad Von Hotzendorf, the two men who pushed the hardest for war on Serbia, were both removed from command after making decisions that were at best questionable and at worst ruinous. Both men would sanction the murder of civilian men, women, and children who were part of neutral nations, and suffer total defeats at the hands of their enemies. Under Moltke, the Schlieffen Plan would be ruined by generals disobeying orders and attacking Russia ahead of schedule, dragging Russia into the fight early.

The soldiers continued living and dying in the trenches for months. After what seemed an eternity, Christmas arrived with no end to the fighting in sight. And then, on the Western Front, a holiday miracle occurred. Men on both sides of the conflict laid down their arms and walked out to engage each other as friends rather than enemies.

The men allowed themselves to talk, and in talking, learned they weren’t so different. The conscripted German soldiers expressed their frustration with this war that their hateful leaders had landed them in. The British and German troops sang carols, exchanged food and small tokens, and played an infamous game of football (soccer for Americans) that the Germans won 3-2. Here’s an interview from the newspaper The Evening Mail with British 6th Cheshires’ Company Sergeant-Major Frank Naden about the events of the day:

On Christmas Day one of the Germans came out of the trenches and held his hands up. Our fellows immediately got out of theirs, and we met in the middle, and for the rest of the day we fraternized, exchanging food, cigarettes and souvenirs. The Germans gave us some of their sausages, and we gave them some of our stuff. The Scotsmen started the bagpipes and we had a rare old jollification, which included football in which the Germans took part.

The Germans expressed themselves as being tired of the war and wished it was over. They greatly admired our equipment and wanted to exchange jack knives and other articles. Next day we got an order that all communication and friendly intercourse with the enemy must cease but we did not fire at all that day, and the Germans did not fire at us.

You can read more journal and diary accounts from the soldiers who lived through the truce here.

Many of the men promised to find each other again after the war as friends, but almost all of them would die before the war’s end in 1918. Before it was all over, 17 million people — soldiers and civilians — would die. Countless more would be wounded. An entire generation of the world’s bravest men would be erased from history. The Christmas Truce, however, has endured in the hearts of the countries most affected as proof that compassion can win out even when the world has gone mad with violence.

Here’s a look at Europe after The Great War finally ended:

Sources:

Catastrophe 1914 by Max Hastings

A The Christmas Truce: Operation Plum Pudding

A Broken World: Letters, Diaries and Memories of the Great War by Sebastian Faulks and Hope Wolf

Soccer in the trenches: Remembering the WWI Christmas Truce by Simon Kuper

Museum Management:

Museum theme by Michael Guy Bowman

Listen to more at: bowman.bandcamp.com

Rachel: Designer #UkuleleWitch @rachelvice

Tour Guide: Emery Coolcats

Twitter: @natmysterycast | Email: natmysterypodcast@gmail.com | Home: https://pomemag.wpengine.com/tag/museum-of-natural-mystery/

Museum of Natural Mystery is part of the POMEcast network, and thanks a million to the ladies of POME for helping this show get up and running! But above all, thank you for listening! We’ll see you next time!