Sometimes, in moments of despair, people turn to mental health hotlines for immediate support. I serve as a crisis counselor for one of these organizations. My role consists of ensuring that my clients aren’t at imminent risk of harming themselves or others (and if they are, working to de-escalate the situation), validating their experiences, and connecting them to relevant mental health resources, all in hopes of helping them find long term support. As someone who wants to become a psychiatrist in the future, this work has been incredibly meaningful to me, and I’ve learned a great deal about different people’s life experiences through the conversations I’ve had with clients.

During one particular conversation, a client was telling me about the profound loneliness she felt. To give me more context on her experience, she divulged that she had been adopted and that this was a source of alienation, as she didn’t feel connected to her adopted family or the other people in her life. I was particularly struck and saddened by the isolation that she felt as an adoptee. For most of my life, I had only heard about celebrities, like Angelina Jolie and Brad Pitt, who had adopted children, and I had perceived adoption to be this altruistic, beneficial experience to both parties. While that might be the case for some folks, I hadn’t ever considered the adoptees’ side of the story or more potentially negative adoption experiences.

Around the same time, I began reading Palimpsest, a graphic memoir by Lisa Wool-Rim Sjöblom on the transnational adoptee experience, for a comics course at my university. From reading this book, I learned more about transnational adoption, a phenomenon in which around 45,000 children a year are adopted across borders. I also learned about how, after being adopted, many adoptees feel as though they are thrown into unfamiliar environments, and struggle to make sense of their new identities. As Lisa points out in Palimpsest, most adoption narratives are framed in a positive light, as they have been written by adoptive parents. However, with transnational adoptees often being “othered” and treated as second-class citizens by locals, I was dismayed to find that the upbeat portrayal of adoption in the media may not truly be reflective of their experiences.

Palimpsest offers a counter-narrative to the mainstream depictions of adoption. Lisa is a transnational adoptee herself, who was adopted by Swedish parents from Korea when she was two years old. After wondering about her biological parents for years, she embarks on a journey to learn more about her life pre-adoption. One challenge that she faces as a Korean adoptee in Sweden comes from people questioning her identity and whether she is actually Swedish. As we see in the three panels below, people make microaggressions toward her, asking the dreaded, tone-deaf question of “Where are you really from?”

In the third panel, a woman expresses surprise to see that despite Lisa’s Swedish name, she is ethnically Korean. These questions draw attention to the fact that she is a woman of color living in an ethnically homogeneous country, calling into question her citizenship and what it truly means to be Swedish.

Lisa also experiences xenophobia, as seen in the image below, when she and her friend get thrown off a bus for being Asian and are called a racist slur. Usually Lisa uses more evenly-size panels in her layouts. In contrast, this incident occupies a wide panel (where there may have been two panels instead), which emphasizes the formative effect this action had on her childhood.

In predominantly white spaces, these types of interactions alienate people of color, driving them to ask if they truly belong in the place that they call home. This, in effect, “others” Lisa— “othering” meaning that her differences are magnified and cause others to treat her differently from locals. Lisa is not alone in feeling this way, as such challenges to Swedish transnational adoptees’ identities have been well-documented by researchers.

This idea of Lisa being “othered” because of her racial identity is further exacerbated by the fact that she was adopted. We see in the panels below how a stranger asks Lisa multiple questions about her biological parents, to which Lisa responds in frustration with a metaphorical speakerphone.

These invasive questions serve as a reminder that adoptees’ stories aren’t really treated as their own. As we saw in this incident, people can overstep boundaries, thinking that it’s perfectly acceptable to ask incredibly personal questions of strangers. They fail to consider that there could be a lot of emotional baggage attached to these stories, as adoptees may have had to deal with separation trauma or other hardships. Research has shown that adoptees typically experience more mental health issues than other individuals, with the difficult circumstances surrounding adoption perhaps being contributing factors to behavioral problems. Additionally, unsolicited questioning from strangers could be emotionally triggering and contribute to worse mental health outcomes.

In society at large, we see an erasure of adoptee narratives when their lives prior to adoption aren’t properly acknowledged. The title of this book, Palimpsest, refers to parchment that’s been reused after the earlier writing has been erased. This is much like the experiences of adoptees whose narratives have been rewritten. In the panel below, we see a class being asked where babies come from, to which Lisa unironically answers that they come from the airport. This innocent response to the question underlies how adoptees may internalize that their life began once they were adopted, which in turn minimizes their lives prior to adoption.

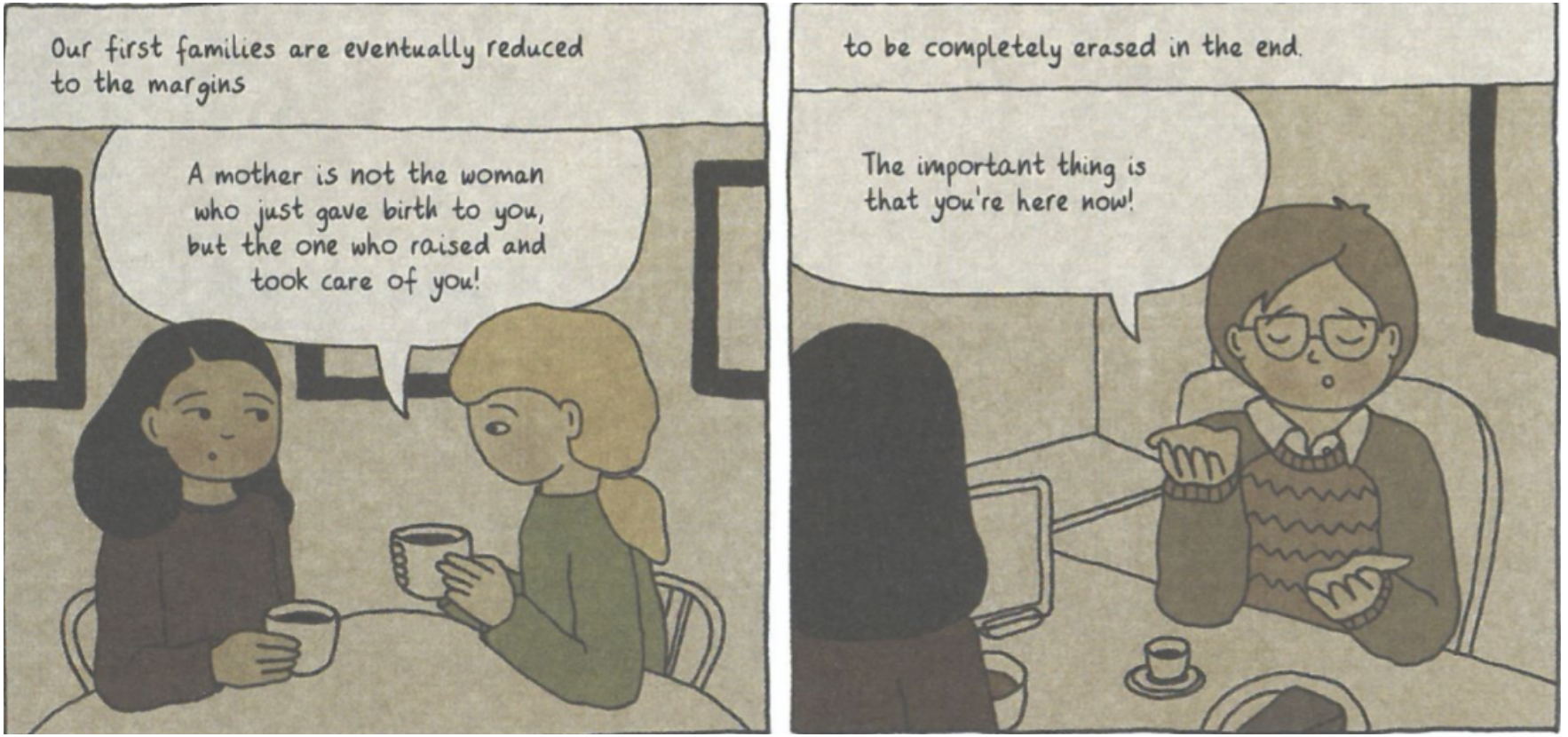

Even comments from Lisa’s adoptive parents inadvertently invalidate the significance of her biological parents. We see how her parents explain that a mother isn’t necessarily the person who gives birth to a child, but rather the person who raises them. In the next panel, Lisa’s dad dismisses her desire to learn more about her biological family by telling her that she’s now with them and that’s what matters.

While these comments may be well-meaning, they brush over Lisa’s desire to learn more about herself. Perhaps Lisa’s adoptive parents don’t know the answers to her questions, and they respond in that manner because they don’t want her to worry about it. However, Lisa argues that events prior to adoption (an adoptee’s birth story) still deserve to be acknowledged. These events not only affect how she is treated by others (as we saw earlier with the person prying about her birth story and Lisa responding while holding a speakerphone), but they may also be important to how she and other adoptees, like my client from the mental health hotline, construct their sense of self.

This sense of self may be further complicated if an adoptee is unable to learn about their life in its entirety. For many adoptees, it is difficult to gather real information about their life pre-adoption. Some adoption agencies abroad are guilty of falsifying adoptees’ biographical information. Lisa herself has an orphan status on her adoption paperwork, which we learn later in the book is completely false as shown below.

With hardly any regulatory oversight in the international adoption industry, adoption fraud occurs with little consequence – though some countries have halted adoptions with one another after discovering corruption. This brings us to the question: what drives adoption agencies to manipulate adoptees’ stories? Adoption is a big business, as international adoption fees can total an upwards of $20,000 or even higher. Agencies have high overhead costs, which includes the salaries for their staff; thus, there is a greater incentive to “market” children for adoption. Lisa also mentions the pervasiveness of saviorism in Western countries: the belief that adoptive parents will provide their adopted children with a better life than what they would have received with their birth parents or at an orphanage. This idea plays out in Lisa’s own life, as represented by the encounter below with a stranger who shares the reasons why they believe adoption is altruistic.

Based on what I’ve learned since reading Palimpsest, I feel that agencies in developing countries are aware of the savior mentality some adoptive parents hold and choose to capitalize on that. By falsely portraying potential adoptees as orphaned, as in the case of Lisa, adoption agencies create a compelling sob story. As a result, adoptive parents perceive these children as being helpless and in need of a loving home. This ultimately gets the child adopted and the adoption agency receives their commission. But at what cost? As Lisa finds, this deception causes her years of pain, as she had lived most of her life believing her parents to be dead. Upon finding out that they are alive, she mourns the lost years she could have spent meeting other family members, like her biological grandmother, who could have shed more light on her birth story and family history but have since passed away.

Since learning more about the experiences of transnational adoptees, I took away that adoptees deeply long for a sense of connection, which is complicated by the fact that they are displaced from their biological family and expected to acclimate to a new environment. Furthermore, they may not know much about their lives pre-adoption, and may be left with questions of who their parents are and what their birth story is. These challenges cause inner turmoil for many adoptees, like Lisa and my client, who struggle to make sense of their identity (or perceived lack thereof identity). Palimpsest overturns the traditional perspective of the adoption narrative, empowering Lisa to take her story into her own hands and tell it for herself. During her quest for closure, she shares how she felt like an outsider in her adopted homeland. While searching for a sense of belonging, she navigates the bureaucratic red tape of Korean adoption agencies, unearthing systemic issues in the adoption industry. There are unfortunately many missing pieces to adoptees’ lives, as oftentimes critical paperwork has gone missing or their biological parents have passed away. However, listening to and amplifying their narratives gives them a say in how their stories are told.

Reading Palimpsest allowed me to make room for different perspectives that challenged my previously-held beliefs about adoption. Knowing these other experiences with adoption now, I want to continue being open to new narratives and use that knowledge gained to treat those around me with greater empathy and understanding. As a future mental health provider, I hope that with this knowledge, I will be more mindful and sensitive to my adoptee patients’ stories. Palimpsest unapologetically explores what it means to be a transnational adoptee, allowing Lisa to finally own her story for what it is, even if there are things left uncertain.