If you’re an average denizen of the digital age and struggle with mental health issues, you’ve probably Googled ways to deal with whatever ails you. (Or what doesn’t ail you, if you have health anxiety like me.)

As for myself, I hope to find community, solace, or an epiphany. Occasionally I’ll come across a soul-quenching quote, a relatable biography, or an insightful article–the mental equivalents of an hour of yoga or a cat nap. But mostly, I find lists. More specifically, “listicles” that are variations on the same themes.

Mental health listicles revolve around the same truisms—eat healthfully, exercise, attend cognitive-behavioral therapy, meditate, and reach out to others. While those tips have scientific evidence backing their efficacy, they often fail to address the challenges in following those routines or how some of us might never know what it feels like to live without our brains figuratively tearing at themselves.

Instead, I prefer stories. Listicles rarely tell stories—they give advice or subtle commands. Stories, both fictional and factual, illuminate the experiences of human suffering. They show, through action and metaphor, the tension between how one’s mind works and how one wishes it would work. They facilitate cognitive and emotional connections between storytellers and readers, connections that might otherwise prove difficult to foster due to social anxiety or physical limitations. In short, stories help us feel less alone.

Listicles are hollow in comparison—they make the path to well-being sound like a public works plan. Mental health isn’t an apotheosis you’ll reach once you do all the right things. Rather, it’s a continual rebalancing act. The other shoe drops, and another shoe drops, and another…and all the while, you try to find some joy or room to breathe.

I once knew a creator of lists and consumer of listicles—someone who saw the other shoe drop as frequently as if it were tap dancing. She read hundreds of self-help books, tried nearly every goal setting system known to humankind, and created decades’ worth of self-improvement lists, going back to her pre-adolescence. The lists ranged from strategies to getting better grades to how to lose weight quickly, all for the purpose of making her feel “good enough.” Her lists, like the listicles seen on blogs, were snappy platitudes that allowed little room for failure or variation from inflexible ideals of womanhood. That person was my mother.

My mother died a few months ago at age 59. She died alone and very lonely, amid her hundreds of self-help books and numerous half-completed journals. She battled mental illness, specifically PTSD, for most of her life. In the last journal she kept, she lamented how difficult it was to follow her various goal lists, which unsurprisingly consisted of eating healthfully, staying physically active, and recommiting herself to her faith. One thing was often conspicuously absent from her planned repertoires: human connection.

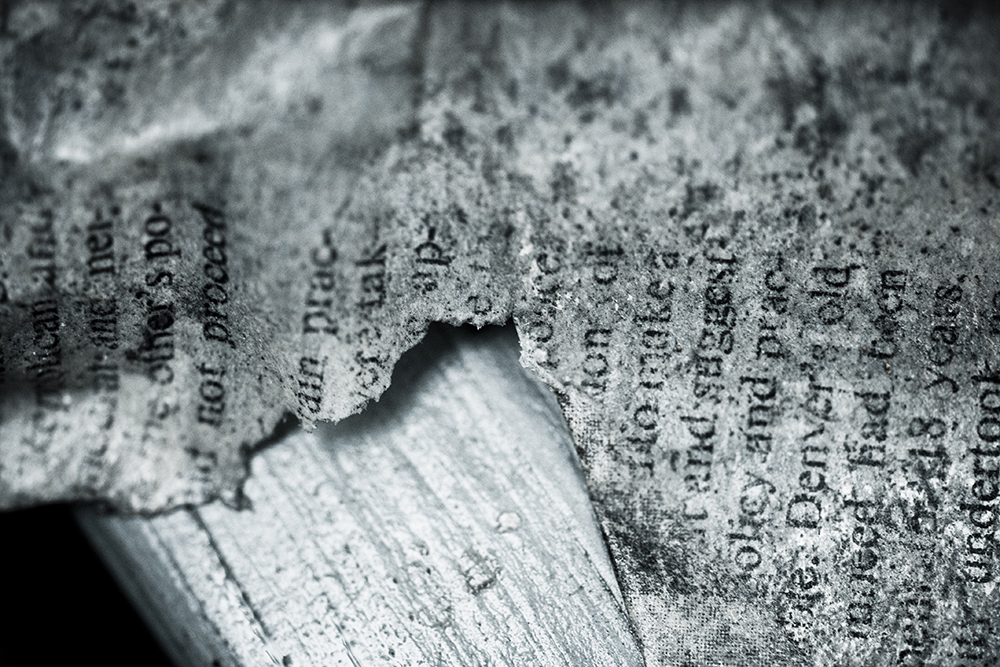

Wary of therapy and loath to burden others, my mom kept her self to herself. Her cries for help are recorded in her journals, work notebooks, and on scraps of paper. Some of her words are directed towards God, and some—mostly recriminations—are directed towards herself. She despaired over not having anyone to confide in and help carry her burdens. Ironically, many people—family, friends, colleagues, and acquaintances—showed willingness to help without solicitation.

While having other people to lean on can make a positive difference, some individuals have a hard time seeing or believing that they aren’t alone. My mother was one of them. While I don’t think human connection is a “cure” for mental illness, I know that humans are an incredibly social species. Recent studies, such as 2017 review by the University of York, show that loneliness strongly correlates with a compromised immune system. Physiologically, we need human connection. It may not eradicate chronic conditions, like dysthymia, bipolar disorder, or schizophrenia, but it’s a strong mental and physical palliative.

Humans are social animals, as well as natural storytellers. Telling stories is an innately social activity. We’ve been creating narratives for so much of our existence, some have lasted over millenia. We viscerally connect to these stories, and the longest lived stories frequently convey the traumatic essence of human experience. For instance, why has Jane Eyre remained so popular over the past two centuries? It’s the story of a woman who faces challenges ranging from loneliness to abuse. How many of us can see a kindred spirit in Jane, and also aspire to emerge victorious in life through sheer will and learned self-respect?

One of the most inspiring aspects of Jane Eyre is that it’s a first-person narrative told by a woman who arguably struggles with mental health issues. Jane fearlessly qualifies her experiences in a society that reduces women’s mental illnesses to hysteria–which is still a problem today. It’s likely, too, that Jane Eyre was written from an autobiographical standpoint, as her creator Charlotte Brontë had remarkably similar experiences and sentiments as Jane.

Through Jane, Charlotte shared her stories; my mother’s stories festered inside of her. Shame, guilt, and anxiety inhibited her from sharing her experiences, even from her best friends and children. She died without attaining the connections she so desperately needed, but wouldn’t seek out of fear. Instead, she reluctantly shunned companionship and desperately adhered to her lists and their promises of a better future. She purchased hundreds of organizers and notebooks, all for the purpose of starting over again and creating structure. Yet, they didn’t give her what she truly wanted and needed–the assurance that she wasn’t alone in the world.

The few times my mom divulged her stories, she expressed both relief and unease. Spilling her secret feelings to me amounted to something that felt like sin—the “sin” of selfishness. I could sense that I was giving her space to do something she needed—accessing human connection in lieu of the cold comfort of goal-oriented lists and hidden, carefully written rants. After her death, I acutely recognized my mom’s reticence to connect in myself. The attendees at my mom’s funeral showed so much love towards her, and such sadness that they were unable to crack open her shell. That experience only steeled my resolve to embrace others and their love in my own life, and dispel my fears of exposing my own vulnerabilities.

10 Natural Depression Treatments, 2 Ways to Stop Worrying and Overcome Anxiety, and many other listicles don’t explore the personal challenges of those who struggle to create routines to combat depression, or desperately talk themselves out of panicked worst-case scenario thinking. The listicles never illustrate the journey to finding peace of mind or meaning in mental anguish, or how some strategies don’t work everyone.

Instead, let’s collectively share our stories in person and online, even if they don’t end with an “ah-hah!” moment of how to get our lives on track. Let’s talk about how working out is a pain in the ass after a long day at work or caring for kids. Let’s talk about how eating healthy is hard when you’re broke. Let’s talk about therapist shopping, and how sometimes a decade of therapy just isn’t enough to make the demons shut up. Let’s discuss how we’re doing all the things to make our lives better, but sometimes life still sucks. Let’s have a conversation—an emotional exorcism while shoes are dropping and in-between.

Featured image source: Pixabay.