Should comics be easy to read?

(“Yes…?” the imaginary crowd answers. “Is this a trick question?”)

When I was in middle school and reading manga scanlations almost exclusively, I resented anything that slowed my comics consumption. And since the online comics buffet was free and my appetite was bottomless, the only thing that really slowed me down was chewing the food. Unclear panel sequencing, crowded word balloons and complicated action shots all bugged me bad. Any pause in the flow seemed like a failure on the part of the artist and a waste of my time. I had 25 volumes of GTO to get through, after all (and after that, 14 volumes of Love Hina, 27 volumes of Berserk, 1,000,000 volumes of One Piece, etc…). The only way through the narrative was forward. So, the cartoonist’s job was to make sure the road was clearly marked and free of obstacles. Right?

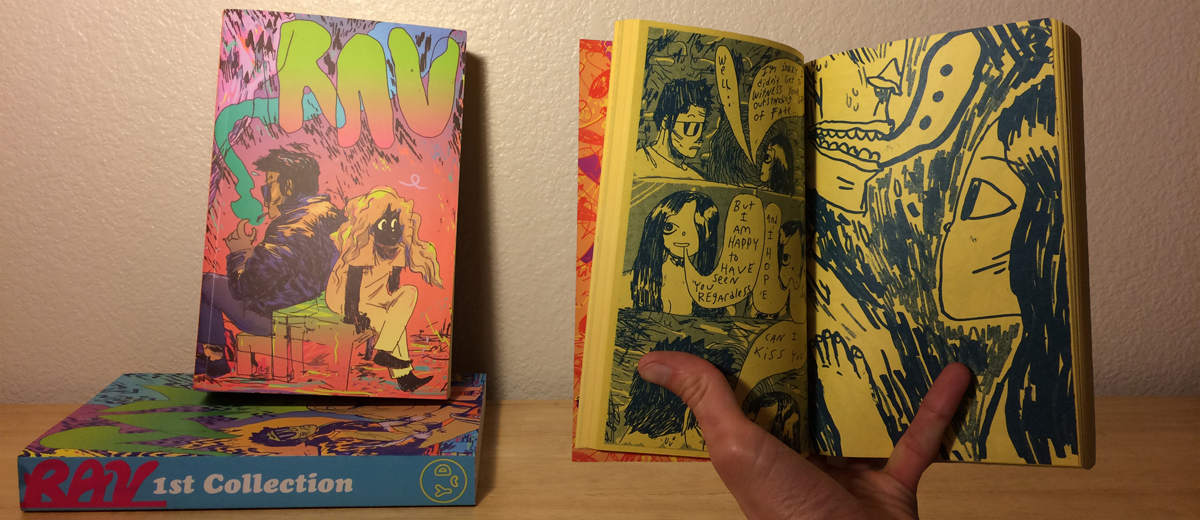

RAV 2nd Collection is the newest volume of collected reprints for Mickey Z’s ongoing and enigmatic minicomic, RAV. The comic follows the separation of a couple, Sally & Juice, and the string of dream-logic events and odd characters that tumble through their lives in the wake of that separation. Stylistically, RAV is reminiscent of cartoonists like Gary Panter or Brian Chippendale, but Mickey Z’s manga influences are also unmistakable. It’s an absurd comic whose absurdities can be drily, devastatingly funny, pointlessly cruel and (shockingly) true-to-life.

RAV is also not an easy comic to read. I worry about overemphasizing this point, but it was the first thing that stood out to me about Mickey Z’s comics years ago and it still stands out to me now. Open any one of her zines and the reader is confronted by, well, a lot. A churning sea of messy lines and digital halftone pours forth from Zacchilli’s pen. Characters emerge from doodled scenery still dripping with the excess of the linework that created them. There is very little negative space. Panels have borders but not gutters between them. The pages of RAV are covered in marks and everything has become an excuse for more. Black fills are scribbled in rather than flatted. Speech bubbles are revised by scratching out the offending word. Even the eraser has been conscripted into the act of mark-making, giving a new, more satisfying meaning to the adage “less is more” by leaving traces in the halftone.

In short, Zacchilli’s horror vacui can be overwhelming. These are comics you must read slowly, because the action in RAV isn’t always instantly and comfortably clear. The signal has to be sorted (sometimes even wrestled) from the noise. Reading a chapter of RAV can feel physical. Immersed so completely in the visual, the reader remembers that looking is an act, not just a passive state. Compared to the manga smoothies of my youth, RAV is a pile of raw vegetables, jumbled on the counter, still dirty from the garden.

So then, what is happening beneath all that noisy excess? A lot of fights for one thing. RAV is punctuated by them with the regularity of any good action comic. But unlike your typical popular manga series, the conflicts in RAV are never fully resolved in terms of understanding. It’s common enough in shonen manga for a fight to start without explanation. But readers are usually rewarded with the missing motivation by the end, in the exposition following victory. In RAV, characters fight for seemingly no reason at all. Juice kills a few of his foes. Others, he ends up hanging out with.

In fact, all of the book’s relationships follow a similar sort of spontaneous and hidden compulsion. The protagonists, Sally and Juice, fall into and out of friendships and romances almost at random. If that seems confusing, then you’re not alone: the characters, too, are in the dark about what’s going on and why. Like the lovers in Dante’s Inferno, they are blown about by winds beyond their control or understanding. Often they say they don’t care. But these repeated declarations of indifference are so obviously a shield that they start to become funny, like a running gag. Because, really, if nobody wants anything, then why does so much keep happening? This contradiction lies at the center of RAV. As characters rotate into the comic’s spotlight, their agency seems to dissipate, as if in the eye of a storm. It’s obvious when other people affect them, or pull them along, yet it seems impossible that their own aimless actions could have any influence. From their own perspectives, Juice and Sally feel disoriented and powerless. But from the other side, they each appear to be the center of gravity for all of the book’s swirling happenstance.

About a third of the way thru 2nd Collection, Sally has swapped her second “boyfriend”, Snake Prince Edward, for her third, Ben — a smiling sociopath with a really cool scar. They conspire over a stolen object called “the power cube” and Ben asks Sally about her desires. It’s one of the few instances in either volume when characters talk directly about themselves. “Power,” she responds at first, but Ben smirks and suggests she already has that. Sally thinks about it. “Yeah…”, she says next, “but I don’t have much… control. I guess control is what I’m interested in.” Who could blame her? It’s a mess out there.

This insistence on the complication of existence is maybe the best thing about RAV, and maybe a lot of other comics that are a bit “hard to read.” Mickey Z’s comics are awesome in the way your friend’s noise band is awesome, but also in the other, older sense, in the way that forces of nature are. They follow a logic which exists prior to and apart from the reading audience. With patience, you can enter into them, but you won’t find the reassuring safety of narrative arcs on the other side. The door you passed through was really an exit, leading out, into the pulsing confusion of a disturbingly familiar world.

RAV, 1st & 2nd Collection, can be purchased from publisher Youth in Decline. You can find more of Mickey Z’s art on her site and be sure to check out her webstore as well, for more zine and some really noice patches and shirts.