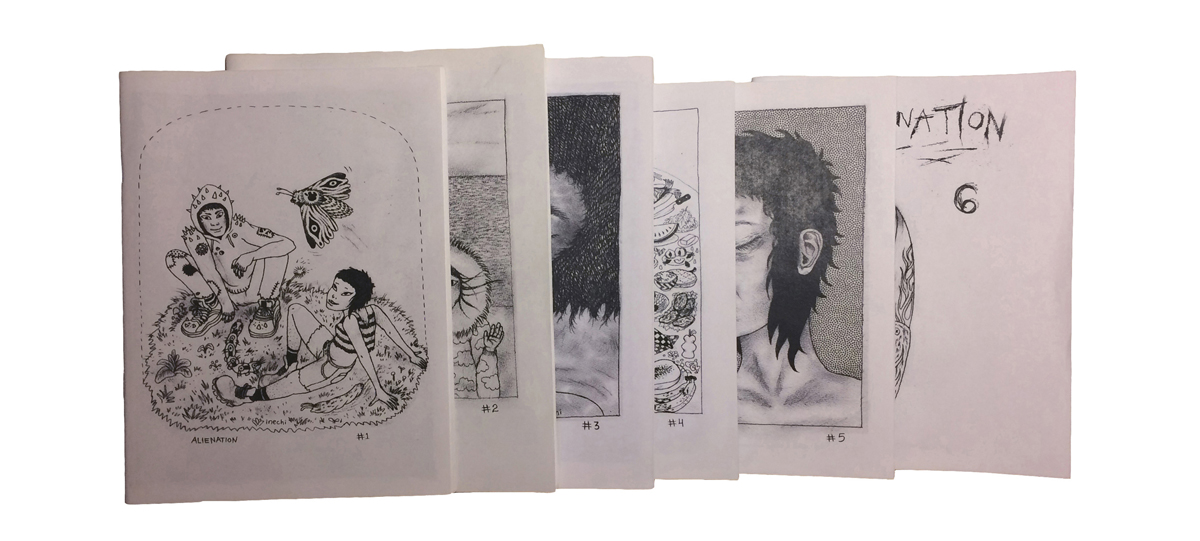

I didn’t put together a “Best Of” list for comics last year, but if I did, Inés Estrada’s Alienation would certainly be on it. I’d actually written about the first two issues of the comic before, but at the time the story was less than halfway complete. Which means, really, that I’ve mostly not written about it. Like mathematically? Either way, the thing deserves more writing about it than it seems to be getting. It’s also maybe your last chance to get in-the-know before a much-deserved reprint by Fantagraphics next year? (Also: this review contains one brief, marked spoiler!)

Elizabeth: I’m pretty sure only until a few years ago, being trapped in a bare room used to be like, torture.

Carlos: …

To point out that Estrada’s near-future story Alienation takes place almost entirely in a barren apartment belies the scope of the comic’s imagination but is nonetheless true. For the great majority of about 200 pages, the protagonist tenants (Elizabeth and her boyfriend Carlos) never venture outside of their depressingly unfurnished cube. This isn’t their fault. It is strongly implied that the hyper-polluted oil town of Prudhoe Bay, Alaska has little to offer them. Once Carlos gets laid off from his job (the last human-run oil refineries are finally automating), Prudhoe Bay may have nothing for them at all. The entire outside world (finally in the long-predicted state of environmental disaster) may have nothing for them. So they stay home. They turn inward. They log on.

Though, in truth, they never really log off. Implanted with “GoogleGlands” which enable them to access the internet with their minds, Elizabeth and Carlos’s reality is perpetually augmented. They live with one foot always elsewhere, the presence of the digital fluctuating only by degree. Sometimes this constant connection just means they have hands-free smartphones, but, if they want, the couple can also immerse themselves fully within any virtual world of their choosing. (One of my favorite visual sequences occurs somewhere in-between the two, when Estrada’s lush pencil drawings of digitally-projected jungle wildlife are contrasted against the sterile walls of the apartment.) They can explore AI-populated MMORPGs, engage in fantastical sex, or dance at historic raves (having set themselves to “MDMA mode”). With the GoogleGlands in their brains controlling sensory input at the point of origin, the experiential difference between the digital and physical aspects of the couple’s existence is largely that one of them sucks.

In my earlier review, I noted that sometimes the fun of a dystopia is the flattering shadow it casts onto its protagonists. The harsher the hellscape, the more admirable the hero is for surviving in it. That’s not exactly the case here. The primary struggle for Alienation’s apartment-bound pair is staving off boredom; they’ve long accepted that they cannot change the world around them. To be fair, this is pragmatism more than apathy. Elizabeth’s technological savvy doesn’t give her the superpowers of a cyberpunk hacker. It does allow her to make a living online (doing erotic camshows), pirate recipes for the apartment’s “iEat” stovetop (which concocts stuff like “sushi pizza” out of “100% glycomycota”) and hatch a plan with an online friend to illegally ship “abortive nanobots” from Finland (more on that in a sec). So, it makes sense those are the things she does. Why waste time spitting in the wind of catastrophic climate change when it’s hard enough to make rent? To focus on the real world would, ironically, be unrealistic. She has so little power there.

Elizabeth may also have less control over her online existence than she’d like to admit. Early on, Elizabeth’s data is breached by a mysterious hacker who sends her creepy messages and even intrudes on her dreams. Nothing seems to have been taken (her bank account is intact) but the incident is disturbing. Even more unsettling is when Elizabeth discovers she’s pregnant despite not having had physical sex with her partner for over a year. SPOILER (highlight to read): In a clever update to the body horror of Rosemary’s Baby, it is eventually revealed that Elizabeth has been chosen by an artificial intelligence to host the world’s first “trans-human” and kickstart the singularity. The dread builds slowly and is compounded by the confusion of her dual-plane existence. Are her dreams and memories part of her mind or are they from the internet? Can the digital tools she uses to navigate the world lie to her? How far can the virtual realm reach back out into the physical? Does the internet owe her anything (and conversely, does she owe it)?

The amount of speculative detail in Alienation is fantastic, but just as important is the porousness of the story’s borders. For every factoid the reader learns about the sci-fi world Estrada has constructed, something else is enticingly hinted at. When Elizabeth looks up travel options for visiting her grandfather, the reader is teased by the search suggestion “why don’t airplanes exist anymore?” Carlos, while playing soccer with a cousin over the internet, drops the bombshell that he stopped playing Call of Duty because the US Army hooks advanced players up to androids fighting in real life wars. His cousin expresses skepticism but not shock and the conversation flows onward. It’s a playful approach that proves that a comic packed with ideas doesn’t also have to be bogged down with exposition. It also, importantly, draws the reader in, engaging their curiosity and hopefully their imagination as they piece the future together alongside the artist.

There’s a tradition in science-fiction of writing stories that are about the present “but more so.” By exaggerating current trends, stories about the future help our own lives become more visible. Alienation is a good example of this, as is Netflix’s Black Mirror (though, for what it’s worth, I think Alienation gets more done in less time and without the scolding). It’s about asking ourselves to wonder now what the future might be like. Then asking what about the world today reflects those future visions. Finally, we can ask ourselves the implied third question: is this future that we imagine in our heads really the one we’d like to live in (and how do we make sure we get a choice)?

Carlos: Yeah? Well, what do you want me to do? Huh?

Elizabeth: Nothing!

Elizabeth: I’m just sick of this shit.

Carlos: I know, but be patient. This is just like a bad dream we’re going to wake up from soon…

Alienation can be purchased directly from the artist here and more art and stuff can be found here.